A hundred years on from Hong Kong’s most calamitous typhoon ever

A hundred years ago...

One hundred years ago on the 18th September, 1906, Hong Kong was hit by a typhoon: “…the most appallingly destructive visitation of the kind that the Colony has ever experienced.”

The 1906

By the time I arrived in Hong Kong in 1968, that typhoon was almost forgotten. I would never have heard about it except for a lie. My boss lied about her age. The idea that she was born on board a ship mid-typhoon, appealed to her compulsion for melodrama. And any old typhoon was not good enough – she told me she was born in The 1906 - the most calamitous typhoon ever.

When I came to write my memoir about Hong Kong, I found she had been born in 1904, a year not notable for any severe tropical storms. I laughed - the 1906 suited her much better.

Typhoon warning systems were well established

By 1906 Hong Kong had a good early warning system for typhoons. During the season, several would pass the Colony. A signal was hoisted in the harbour when one was in the five hundred mile range. Often it was lowered as the storm blew itself out over the China Sea. But if the typhoon did close in, a second signal went up indicating that it had moved to within three hundred miles. Then everyone prepared for the worst. The final signal was the typhoon gun which was sounded when the storm was about to hit.

At the signals, the Colony swung into action. Steam launches towed chains of big flat-bottomed lighters into shelters, while smaller sampans scudded off to find safe havens. Sails and awnings were reefed and everything was battened down. Ships at anchor prepared to get up steam and either made for the open sea or paid out more cable to safely ride out the storm in the harbour.

What made the 1906 so deadly was not just its intensity, it was its speed. There was only half-an-hour between the first signal and the final gun. Nothing like it had ever happened before. Usually there were several hours between each signal.

Never before had one hit with such speed

Captains who’d spent the night ashore were astonished to be woken by the sound of the typhoon gun. They tried desperately to get back aboard their ships, paying motor-launch skippers enormous amounts to take them out on the harbour. Even then it was too rough to go alongside and crewmen had to throw lifelines into the water and drag their officers aboard.

Noise exploded around the Colony. The wind blew at a hundred-and-fifty miles an hour howling along the shore, shrieking through the streets and roaring up mountainsides. The roofs of godowns – huge storage sheds – flew off and their walls collapsed. Everywhere signs were falling, shutters banging, glass shattering, rickshaws overturned and sedan chairs were thrown about “like feathers”.

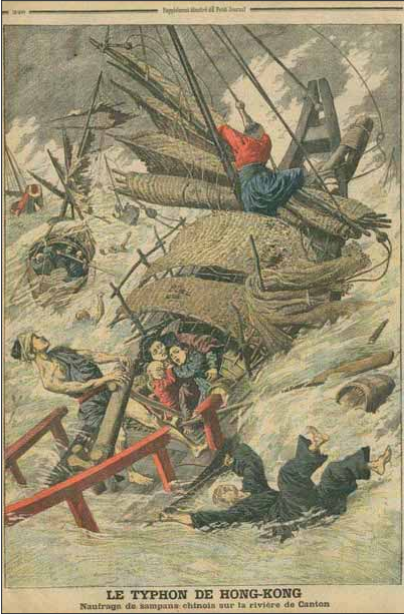

The harbour was obliterated in a terrible fog of driving rain fused with scud and spindrift whipped from the wave tops. All along the seawall, sampans and lighters were dashed to pieces. Piers and wharfs started to collapse one after another… “like a house of cards.”

Eyewitness Account

An extraordinary eyewitness account was written by Captain Outerbridge of the China Navigation Company’s steamer Taming, which came safely through the ordeal. He crouched behind steel plates in the bow of his ship with two other officers. They peered through blinding rifts of mist, desperate to gauge if their mooring was holding.

“Every now and then a ship dragging her anchors as if they were of wood, slid past us, fortunately clear. Until they were right upon us we had no warning and they passed in a flash…

But the worst feature of all was seeing the small boats go flying past bound for what we knew was destruction. There was nothing we could do. Our own fate was in the balance that trembled with every squall that came down heavier than the one before... In the sampans, where entire families of Chinese live their whole lives, women would hold out their children to us begging in mad appeals that we could not even hear, only guess at from the expression of their faces, as they were whirled along the side of our ship, in much the same way that a piece of sea weed is hurled by the crest of the sea. We could only look at them and pity them, and there we crouched for more than an hour and most of the time the tears were streaming down the faces of the three of us as we looked at the poor creatures going to death and could not lift a hand to save them.”

And then it was gone

The typhoon left almost as quickly as it had come. Within three hours it was over.

It was calculated that half of all the Chinese craft in the waters of the colony were lost.

Ships entering the harbour over the next days brought in survivors plucked off floating pieces of wreckage but mainly it was the dead that the sea gave back.

The number of people who perished was never established, but it was in the thousands and may have been as many as ten thousand.

Tales of gallantry, extraordinary rescue and random luck were rife afterwards, but most never had the chance

to tell the tale.

The full account – The calamitous typhoon at Hongkong 18th September, 1906, published by the Hong Kong Daily Press, 1906: http://ebook.lib.hku.hk/HKG/B36228084.pdf